Atmospheric optical phenomena represent a fascinating and complex natural spectacle, evidence of the interactions between sunlight, the atmosphere and the particles that are inside it. These events, such as rainbows, halos, mirages, green rays, etc…, not only enrich the visual landscape of our planet, but also offer valuable opportunities for scientific study to understand the properties of the atmosphere and the processes of light propagation in the atmosphere. In this article, we will explore their main manifestations, analyzing their physical causes and the climatic conditions that favor them.

Photometeors

In astronomy, the term meteor, from the Greek metéora “celestial phenomenon”, usually refers to a luminous phenomenon resulting from the crossing of the atmosphere by an extraterrestrial solid called a meteorite. In meteorology, however, a meteor is associated with an event observed in the free atmosphere or on the Earth's surface. It can consist of a liquid or solid precipitation, or an optical, electrical or sound manifestation. Meteors are then classified into hydrometeors (fog, snow, ice, rain...), litometeors (smoke, dust storm...), electrometeors (polar aurora, lightning...) and finally photometeors (corona, halo, parhelion, rainbow...). The latter term refers to a luminous phenomenon produced by reflection, refraction, diffraction or simply by the interference of solar, lunar or astral light with particles present in the lower atmosphere (troposphere).

According to the World Meteorological Organization, photometeors can be classified into phenomena that form: on or inside clouds (halos, coronae, iridescence and glories); inside hydrometeors or in litometeors (coronae, glory, rainbow, crepuscular rays), in free air (mirages, sparkle, green ray).

Rainbows

Rainbows are undoubtedly one of the most famous optical manifestations of the atmosphere. Aristotle, in Book III of his Meteorology, spoke of only three colors: red, green and blue. Dante Alighieri instead claimed that there were seven. The first Islamic scholars instead described the rainbow as if it were simply three-colored: red, green and yellow. In the Renaissance it was established that there were four colors: red, blue, green and yellow; while in the 17th century it was hypothesized that there were five: red, yellow, green, blue and violet. Scientifically they were studied for the first time by the mathematician Descartes in 1637, who understood the mechanism of the passage of light in water drops and calculated the angular position of the primary rainbow. He understood the importance of the sphericity of water drops in the mechanism of formation of the iris and also determined that the center of the arc is the antisolar point. Before him it was believed that the drops had the shape of tears. Now we know that rainbows are made up of an arc with the infinite colors of the rainbow, with the variable radius of the primary arc from 39° to 43° and with the center at the antisolar point. They are formed by the internal reflection of solar or lunar light in water drops: when the beam of light enters a drop it is refracted, reflected in the drop and then refracted again (when it exits the drop) just like in a prism. If two reflections occur in the drop, instead of just one, a second (secondary) arc is formed with colors symmetrical to the first and with a variable radius from 50° to 57°. In this case the second arc will have a thickness equal to double the first, but a brightness reduced by 43%.

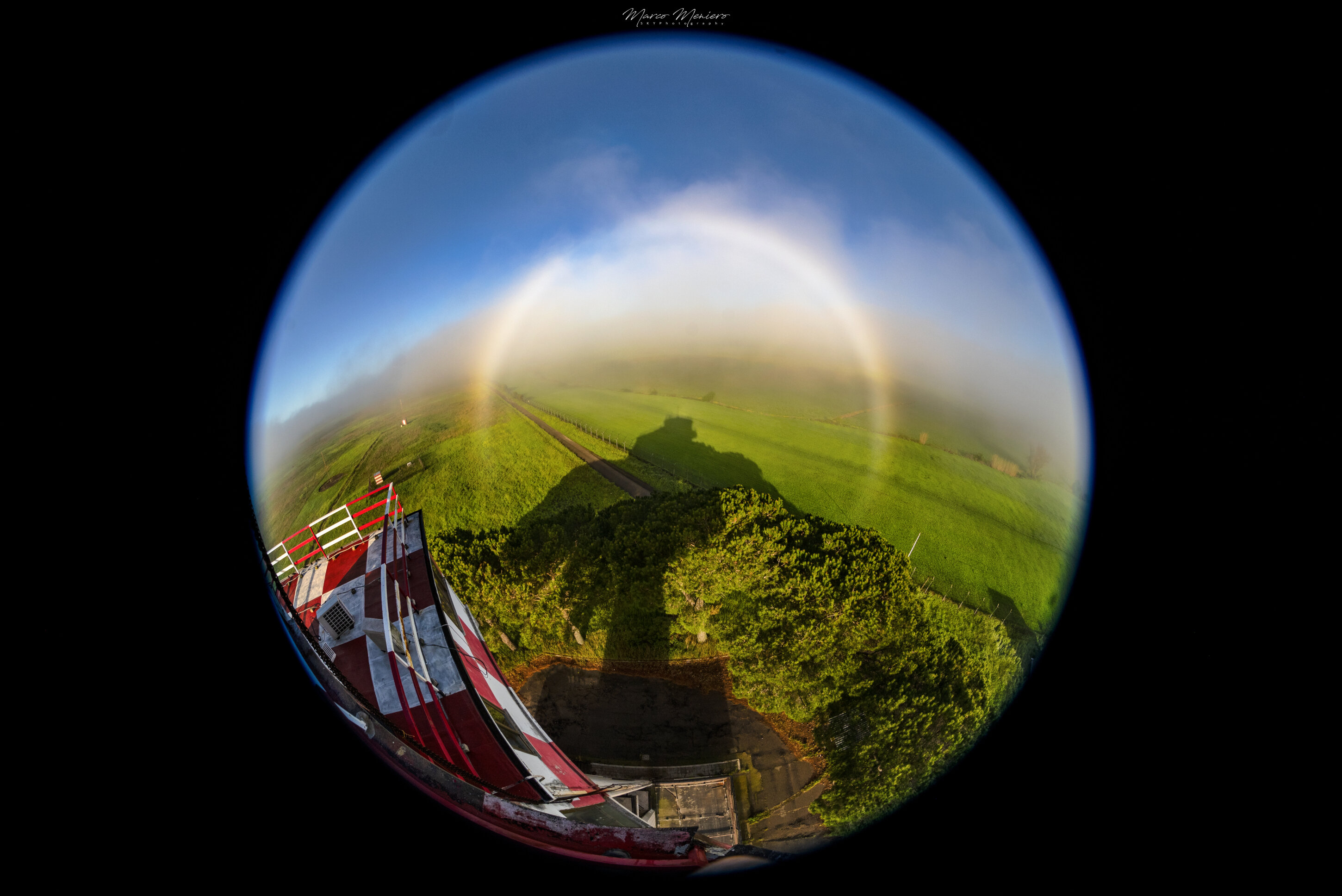

The Fogbow

The chromatic intensity of the rainbow is determined by the diameter of the water drops: large dimensions in the order of 1.5 mm or more create very contrasting colors, while smaller diameters of up to 0.1 mm make the rainbow pale and evanescent; if instead the drops have dimensions less than 0.05 mm, the primary bow appears whitish and barely visible. In this case we are no longer talking about the common rainbow, but of the rare “white fogbow”.

Supernumerary bows in rainbows

Supernumerary bows can also form, or tenuous parallel filaments of color that develop in the lower part of the primary bow. For simplicity we can consider that their origin is due to spurious reflections inside the large water drops when they contain pollen grains, atmospheric dust or simply oscillate and change shape in the fast and random rotations during precipitation.

The “Alexander Band” in rainbows

The “Alexander Band” is a very dark band between the primary and secondary arcs; it takes its name from Alexander of Aphrodisias, who first described the phenomenon in his “Chronicles” in 200 BC. The band generally appears darker than the regions outside the arcs because the light in that area undergoes a deviation similar to polarization: in the primary arc, the light rays undergo a deviation towards its interior, producing a lighter area. In the secondary arc, a similar but inverted process occurs, so the lighter area appears outside the second arc. The superposition of the two effects creates the Alexander Band.

Halo phenomena

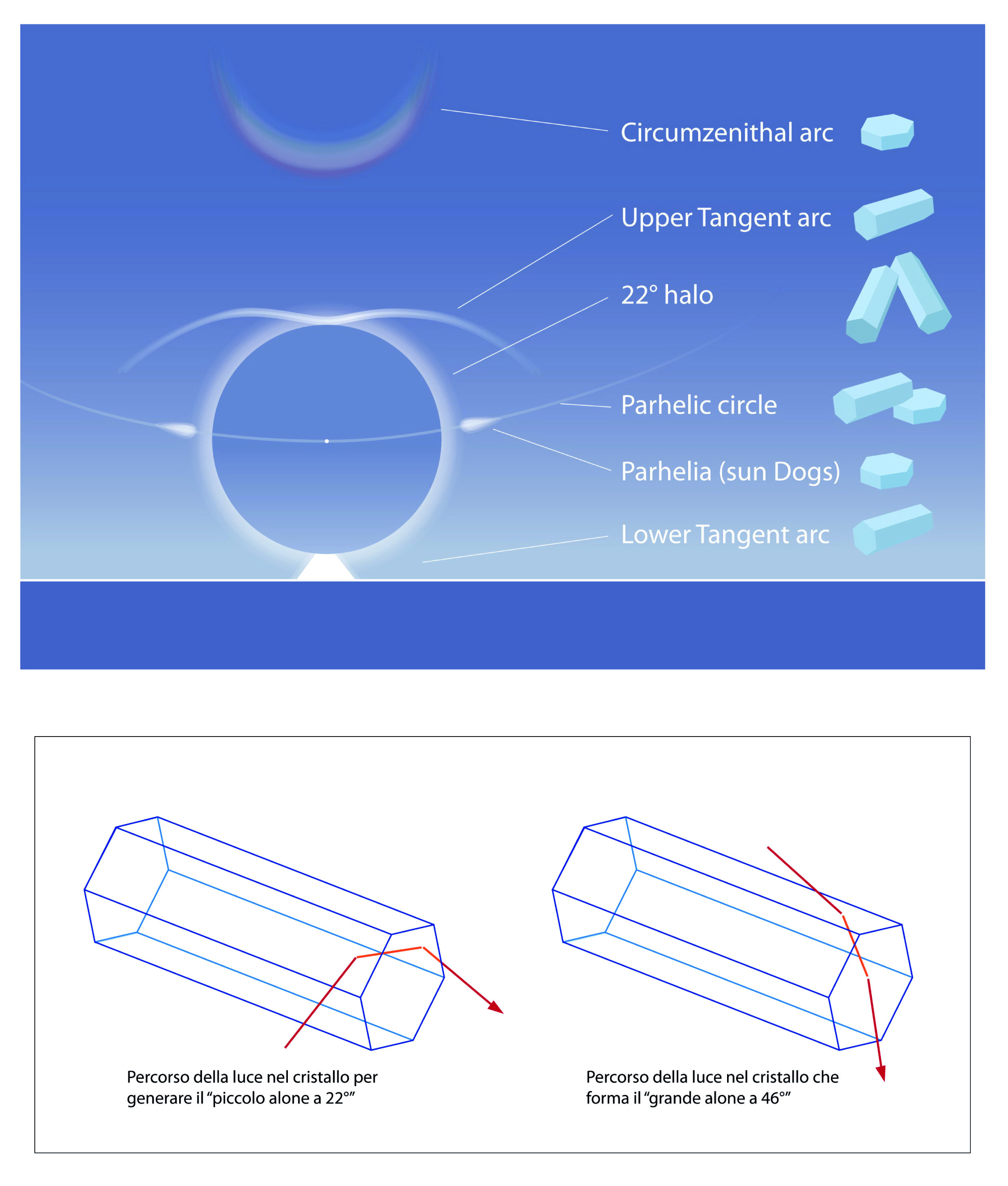

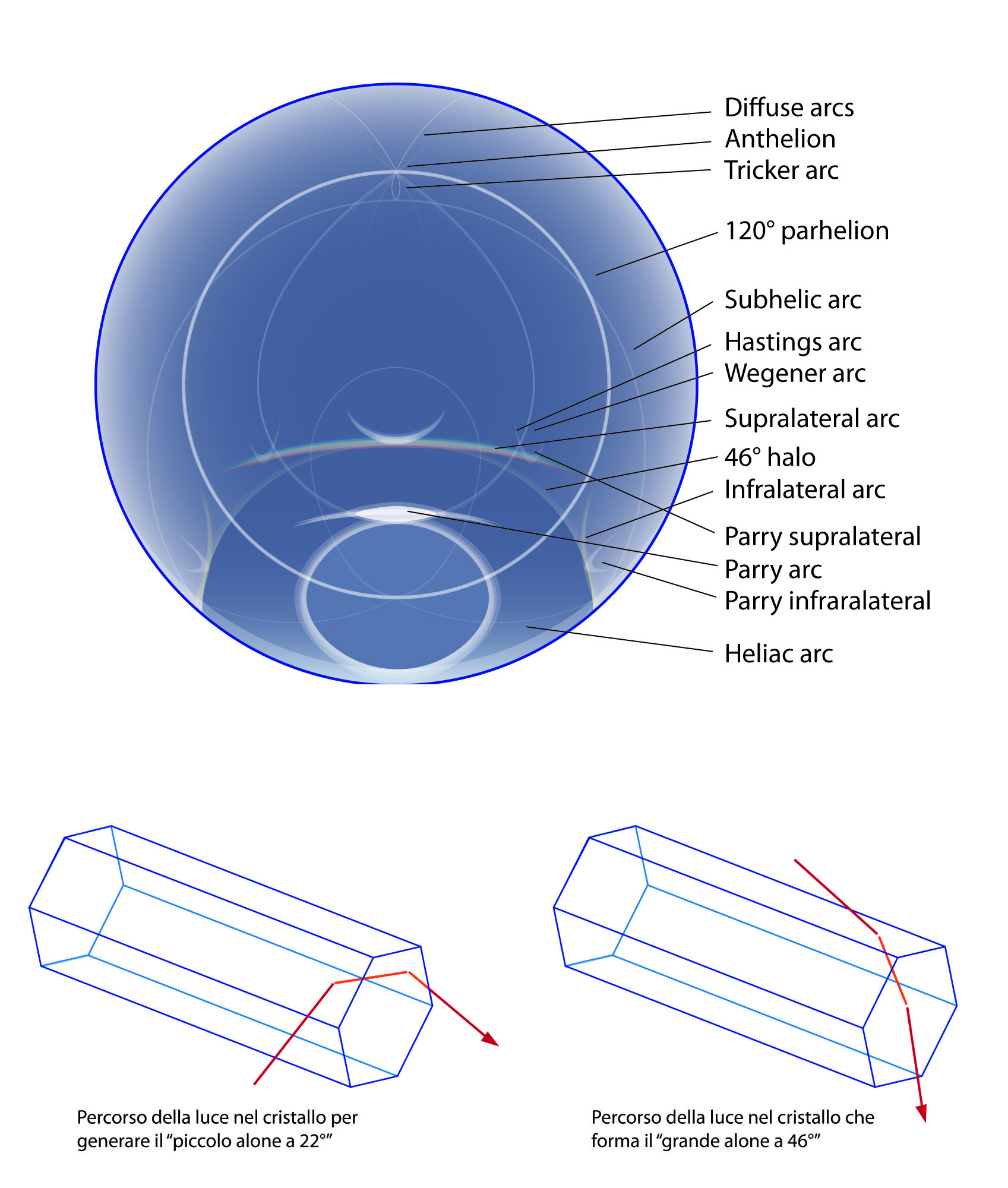

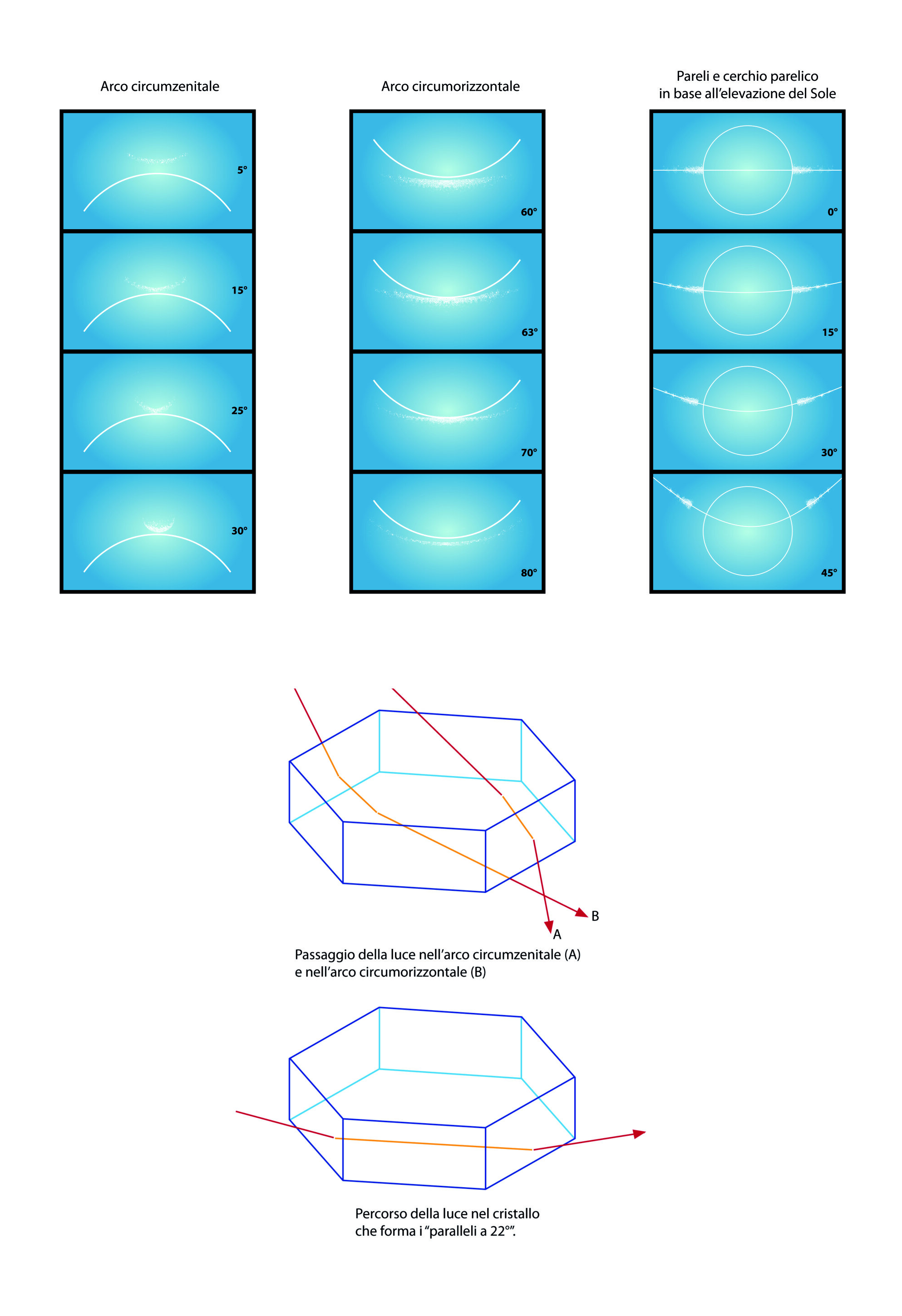

Sunlight or moonlight can be refracted and form halo phenomena when it passes through the hexagonal ice crystals of cirrus clouds. Halos differ from each other based on the elevation of the light source and the shape and movement of the ice crystals. Halos appear on thin cirrus clouds as large rings of light around very bright sources such as the Sun, the Moon, the major planets and the brightest stars. The extent of the halo depends on how the light is refracted as it passes through the ice crystals and how the ice crystals are oriented. The direction of refraction is not random, for example horizontally oriented hexagonal ices have a refraction angle of 22 degrees between the direction of light entry and exit.

Main halos can have a radius of 22° or 46° from the Sun and their thickness can vary from a minimum of 9° to a maximum of 35°. There are also rare cases of halos with radii less than 22°. There is a vast case history of halo phenomena that are called arcs and depend on the shape and arrangement of the ice crystals; they can appear at very distant angular distances from each other and can have the center of their curve in the Sun, in antisolar or zenithal positions. At the lower edges of the larger halo, infralateral arcs can appear symmetrically.

The parhelion (also known as sun dog or false suns) can be considered a halo phenomenon consisting of two bright spots placed at the same elevation as the Sun (or the Moon, but in this case it is called a paraselenium). These spots have the typical color of the iris with red towards the Sun and are placed at fixed angular distances from the light source. Parhelions also form due to the refraction of light in horizontal hexagonal ice. The distances from the Sun are generally equal to 22°; However, in rare conditions, a pair can also form at 46° and 120° from the Sun.

Sun pillar

A Sun pillar is a bright column that extends from the solar disk downwards or upwards and usually occurs when the Sun is close to the horizon. It is caused by the reflection of sunlight by horizontal ice crystals.

The clouds that generate it are made up of flat, large ice like tiny mirrors, or pencil-shaped crystals that reflect the light. Often before dawn, sunlight begins to illuminate these tiny ice more and more with the solar disk still below the horizon. The colors of dawn become deep red. The ice moves slowly through the air like falling leaves in autumn, remaining parallel to each other. However, only those few that are in a horizontal position reflect sunlight towards the observer and therefore illuminate the sky more intensely above the Sun, making the entire sky red. Light columns can also be generated with different light sources such as artificial lights (car headlights, street lamps), the Moon and stars with negative visual magnitude.

Atmospheric dispersion (scattering)

Only 80-85% of the Sun's photons manage to directly reach the ground without being subject to external interference. The remaining 15-20% instead undergo the phenomenon of scattering (dispersion) when they come into contact with atmospheric molecules and aerosols. This phenomenon is due to the fact that each material has a refractive index that varies depending on the frequency of light that strikes it and it is precisely this interaction that determines the colors of the sky. To understand its effects, we must understand what happens in the particles that make up the atmosphere: which is composed of a mixture of gases that filters the light coming from the Sun, splitting it into individual wavelengths and polarizing it.

Aureole

An intuitive example of scattering variation is the phenomenon of the Aureole. To understand this, you have to observe the Sun and pay attention to the glow it generates: on some days there may be a greater glow, on others it may appear more point-like and stand out clearly from the background sky. The glow, or halo, is caused by the scattering of atmospheric particles such as dust, smoke, humidity, pollen and water, which spread the light to the sides of the solar disk. Large quantities of these molecules produce a very pronounced Aureole.

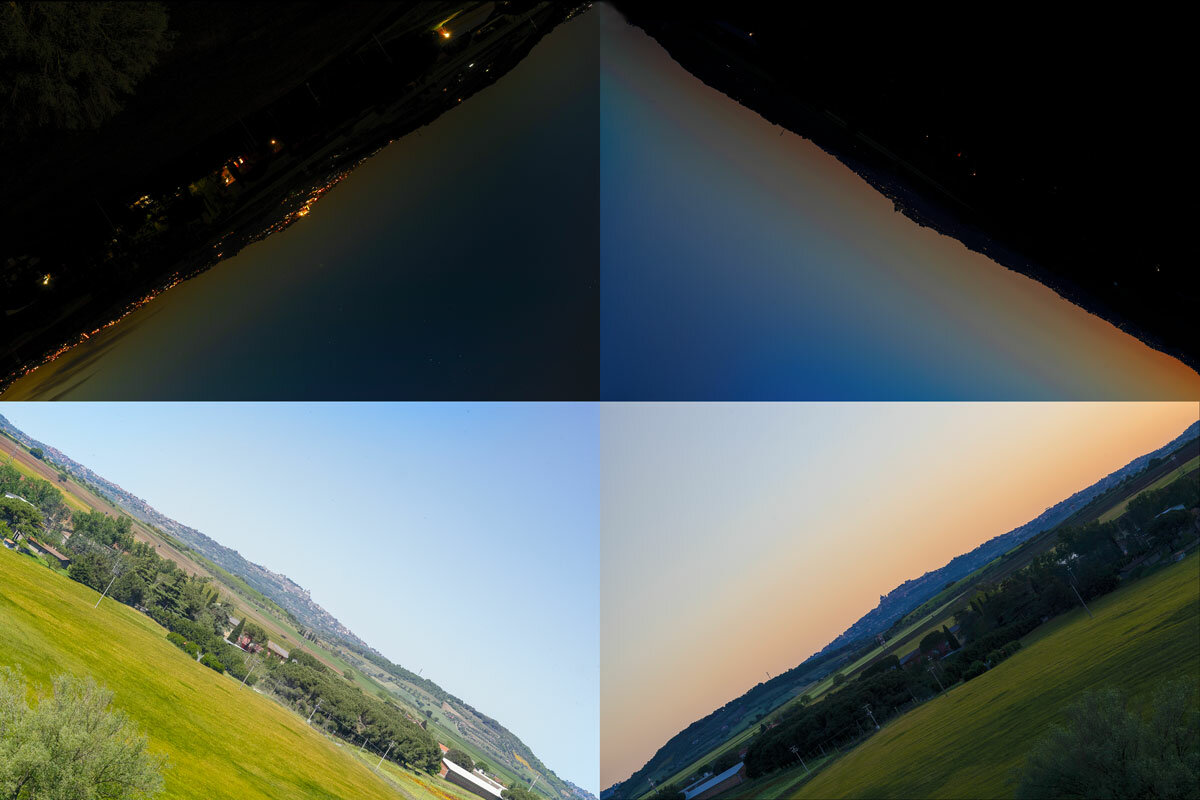

Golden hour, blue hour

Other examples of scattering are the visibility of the Earth's shadow cone and the Enrosadire. Even in the world of photography we have an example of scattering: we are talking about the golden hour and the blue hour. The first, also called magic hour or golden hour is the hour after sunrise and the one before sunset. During these periods the light has a very warm dominant and makes the photographic details noticeably soft, intense and golden. The shades that can be photographed vary from red to purple, the shadows are very long and the photographs are rather emphatic.

The term blue hour, which derives from the French heure bleue, refers to the period of the day after dusk of about fifteen minutes in which the diffused light is colder and therefore photographers are able to obtain images with more penumbras, faded colors, a more intense sky and cold dominants.

As we have seen, the sky becomes red during sunsets and sunrises, due to refraction and scattering. These factors affect the propagation of blue light, decreasing it in favor of the red component and in some cases of the green. For these reasons, clouds just above the horizon turn red even in the presence of clear skies.

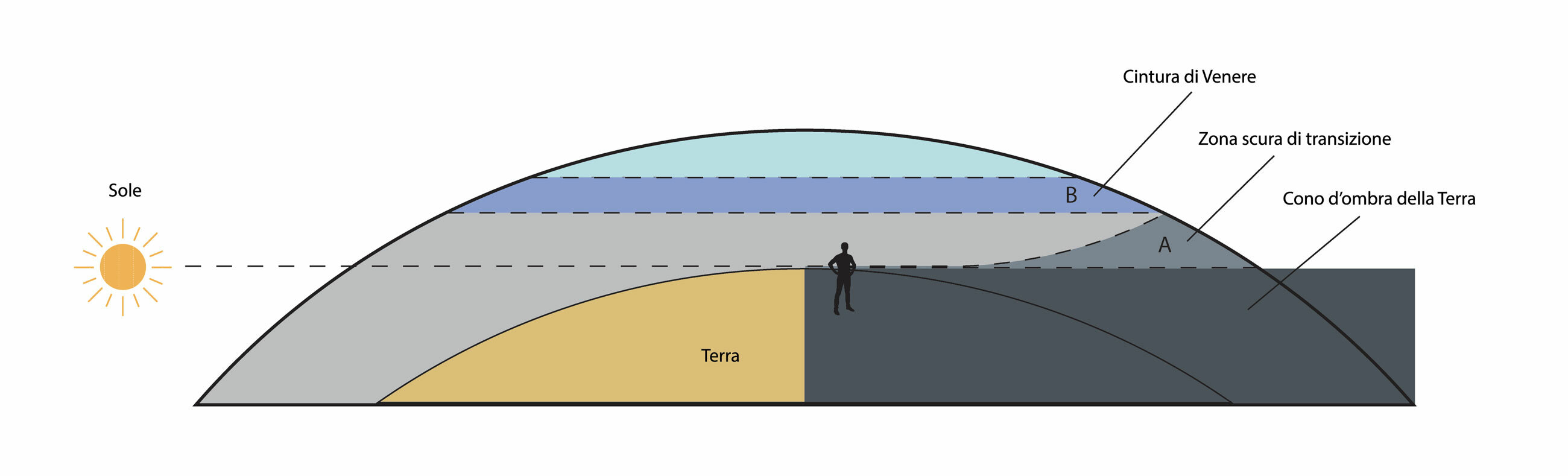

The Earth's shadow cone

The Earth's shadow cone is the projection of the shadow of the Planet Earth on the celestial vault. It rises in the East after sunset, or sets in the West before dawn and can be observed as a dark blue band, low and wide on the horizon, squashed between the horizon and the anticrepuscular arc. When the sky is particularly clear, the upper edge of the shadow turns red and takes the name of Venus' Belt. This name probably alludes to the "cestus", a belt or band for the chest of the ancient Greek goddess Aphrodite, Venus for the Romans.

Enrosadira

When the highest mountain peaks are illuminated by the light of the Sun, after it has already set for 30 minutes, they take on a pink color. This coloration becomes very evident when it contrasts with the dark blue sky and the Shadow Cone. The phenomenon is also known as alpenglow or alpenglühen and varies from day to day based on the weather conditions.

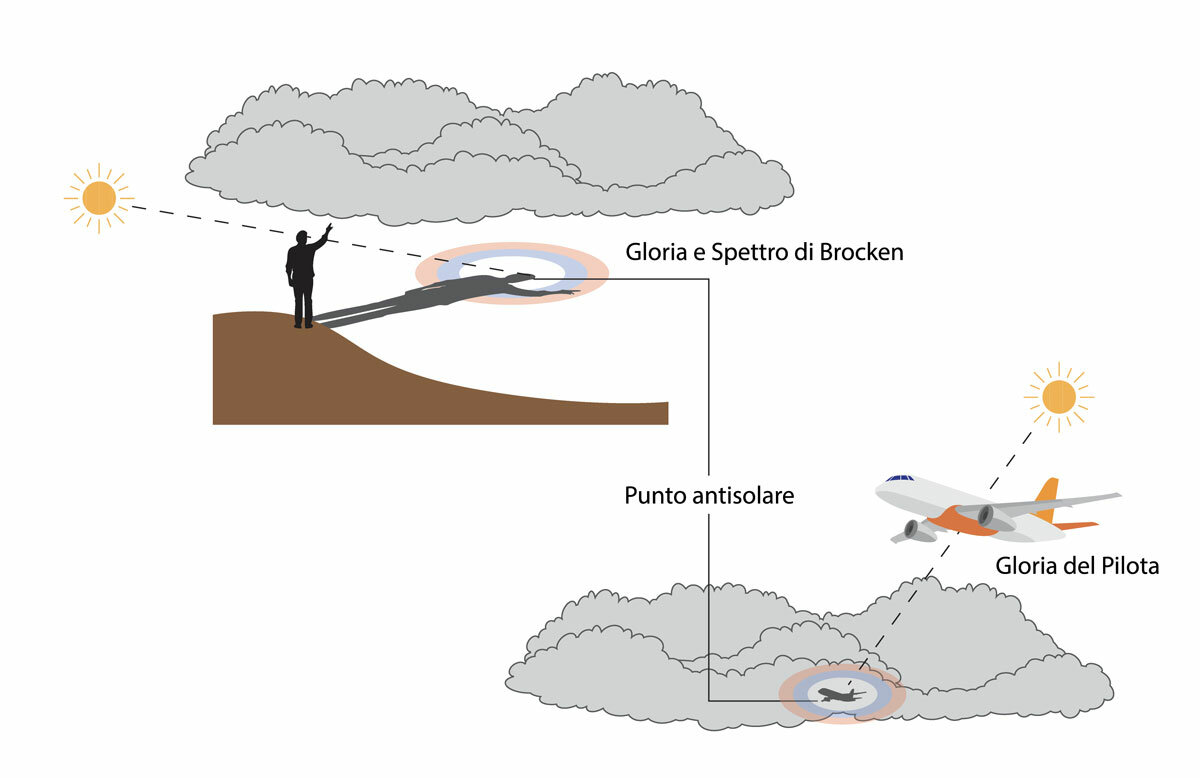

Gloria and Brocken Spectrum

Suppose we are standing on a hill, and the Sun or Moon shines behind us. Our shadow is projected onto the fog below and is apparently transformed into a pyramid-shaped silhouette with its apex at the antisolar point exactly where the shadow of our head appears. This shadow is called the Brocken Spectrum. If the apex of the shadow is surrounded by a bright halo then this brightness is called Gloria.

The Gloria is an antelium, or a phenomenon that occurs in the opposite direction to the star. Many people think that the Gloria and the Brocken Spectrum are the same phenomenon, but this is not the case. They are two different and distinct phenomena: the Spectrum is simply the shadow of the observer and could be assimilated to an anticrepuscular ray formed by the shadow itself. The Gloria is composed of the Aureola and the concentric luminous rings visible inside it. It is hypothesized that the aureola drawn on the heads of the Saints in the history of art are an interpretation of the physical phenomenon of the Gloria.

Scintillation

The apparent brightness, color and position of the stars undergo variations due to the fluctuations of the refractive index in the portions of the atmosphere crossed by the light rays. Scintillation is more pronounced when the light travels longer distances in the atmosphere so the twinkling of the stars is more evident near the horizon than at the zenith.

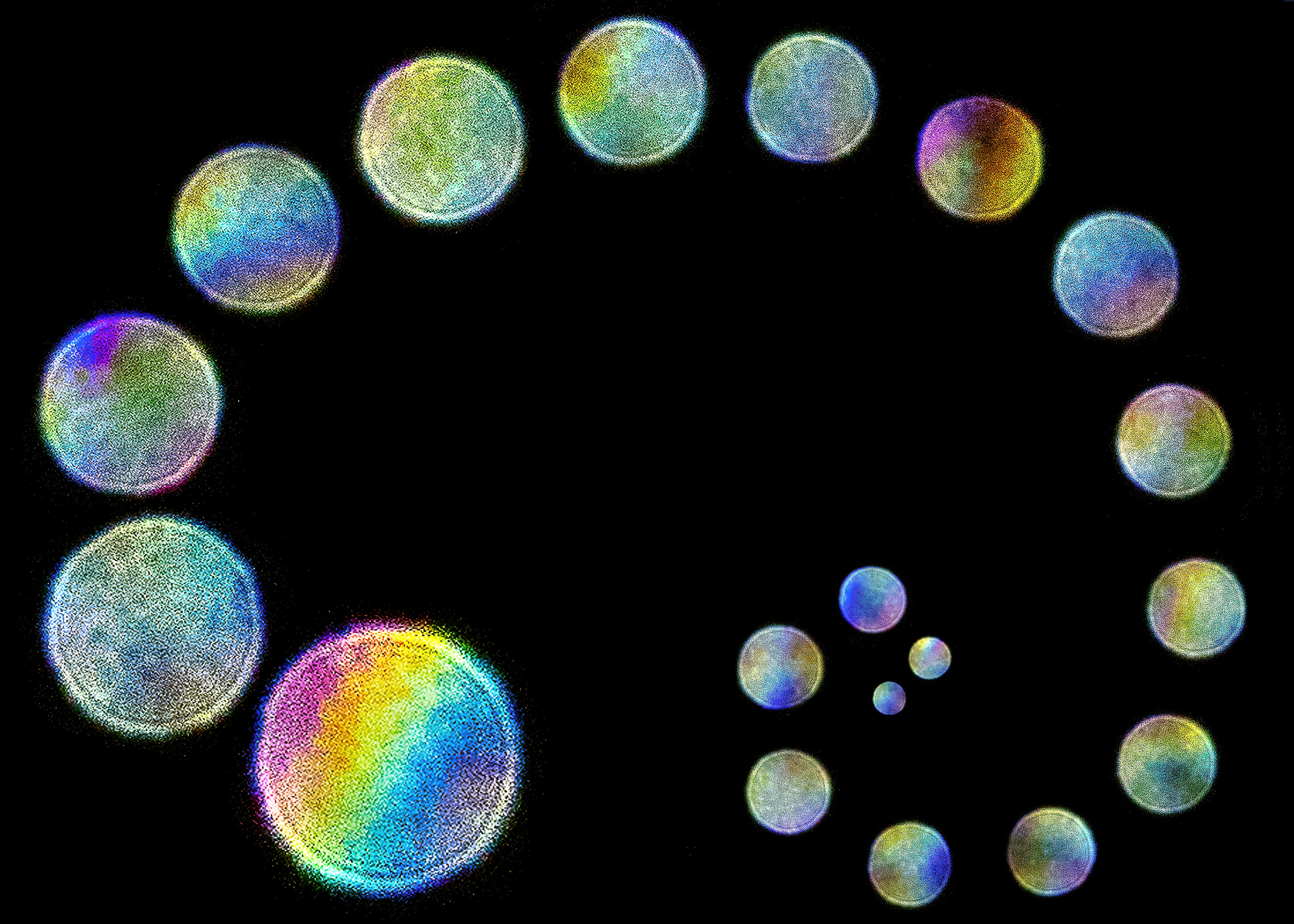

Corona and iridescence

When the light of a star passes through the ice and water drops in thin clouds, colorful colors can be created on the clouds in collected shapes such as coronas, or dispersive such as iridescence.

The colors depend on the diffraction of the light caused by very small particles that are slightly larger than the wavelength of the light. The exact angle between which the maximum and minimum of the light intensity varies depends on both the size of the atmospheric particle and the wavelength. The shape of the particle is not decisive in the diffractive process, but it is important that the cloud contains both ice crystals and water droplets. If the size of the droplets and ice are similar then round coronas are formed, otherwise the corona appears frayed or the light generates only iridescence.

Mirages

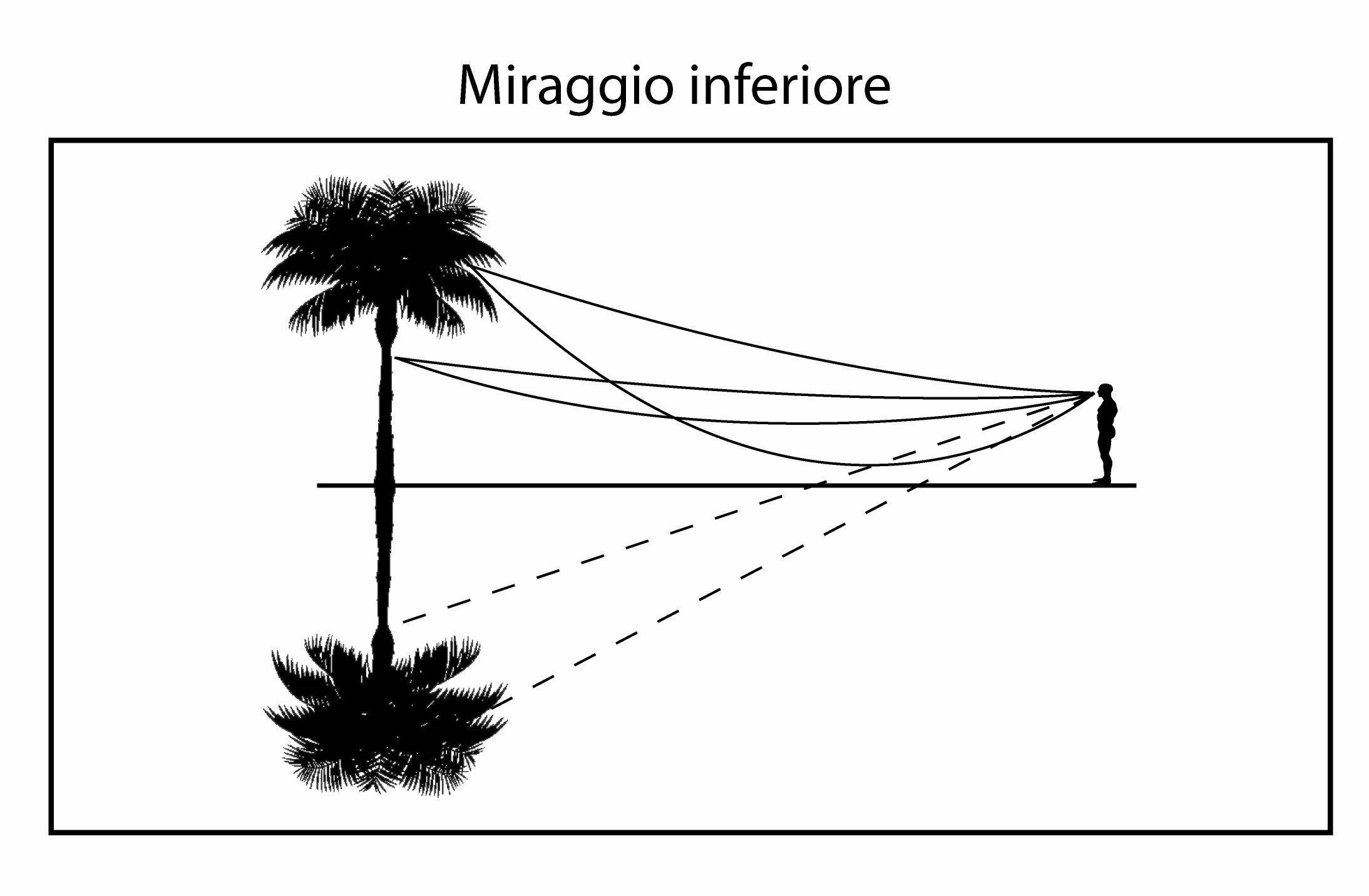

Mirages are physical optical illusions produced by differences in temperature between different layers of air and between these and the Earth's surface. Under certain conditions, objects and panoramas placed at a considerable distance from the observer can produce virtual images and be observed distorted, doubled or upside down. Mirages can occur during the day and at night, mainly in the following ways: "inferior mirages", "superior mirages" or with more than three refractions.

In the case of inferior mirages, the lower atmospheric layers, in direct contact with the ground, heat up more than the upper ones; consequently, if no ascending currents are produced, a real carpet of unstable hot air is created on the ground and therefore a vertical variation in air density such as to produce refraction and reflection phenomena. The light rays that encounter this thickness of air do not propagate in a straight line, but curve upwards, producing a virtual image upside down.

The most common example of an inferior mirage occurs in the summer on asphalted roads, where temperatures can reach 70°C in the first 15 cm above the ground. From a distance, it seems that the road is wet: but what you see is the sky reflected by the layer of hot air above the asphalt. This type of mirage is called a shimmer.

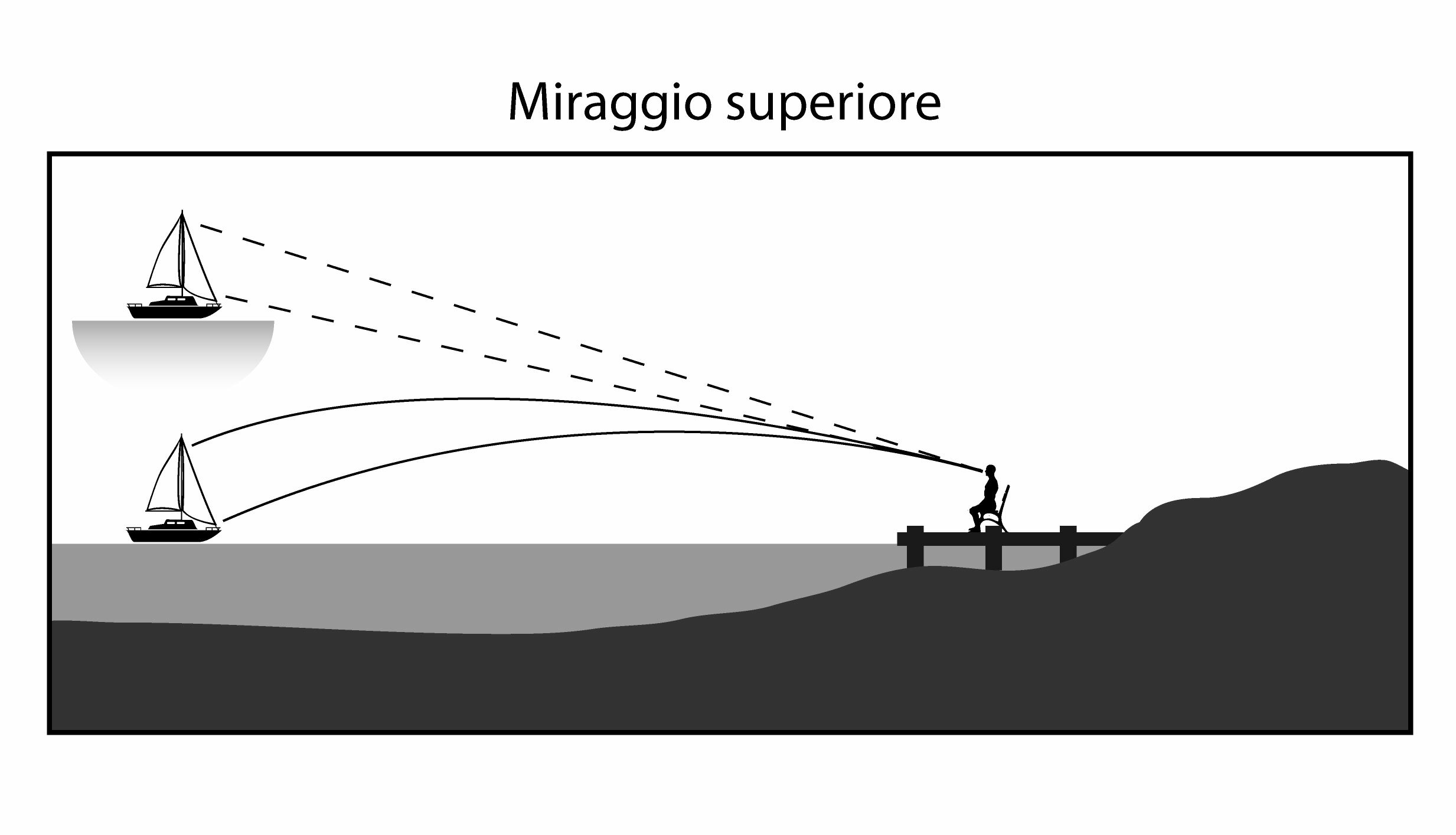

The superior mirage, on the other hand, is generated when the layer of air is colder than the ground and denser than the upper layers of air. The visible effect is the opposite of the inferior mirage.

The physical principle of superior mirages is identical to that of inferior mirages, with the difference that the thermal gradient is inverted, so that the air temperature increases from the bottom to the top. In this case, distant objects and panoramas appear projected into the sky, straight or upside down.

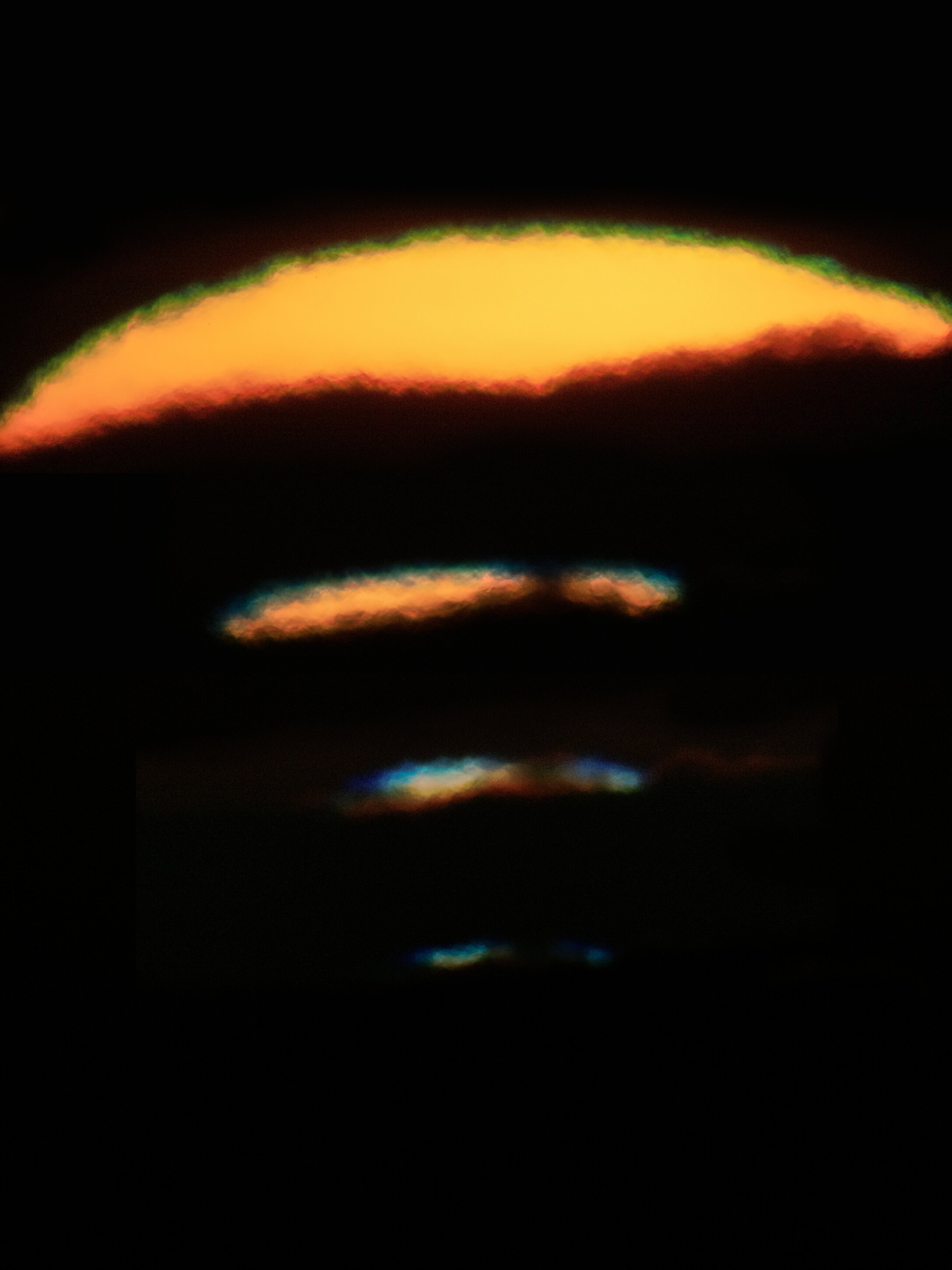

Solar Disk Mirages

The “Omega” Sun illusion (or “Etruscan vase”) is an example of an inferior mirage, which consists of seeing the solar image that takes the shape of the Greek letter Omega. It is made up of the real solar disk, which is however joined, in the lower part, to its virtual image reflected by the sea and by a layer of hot air just above the horizon.

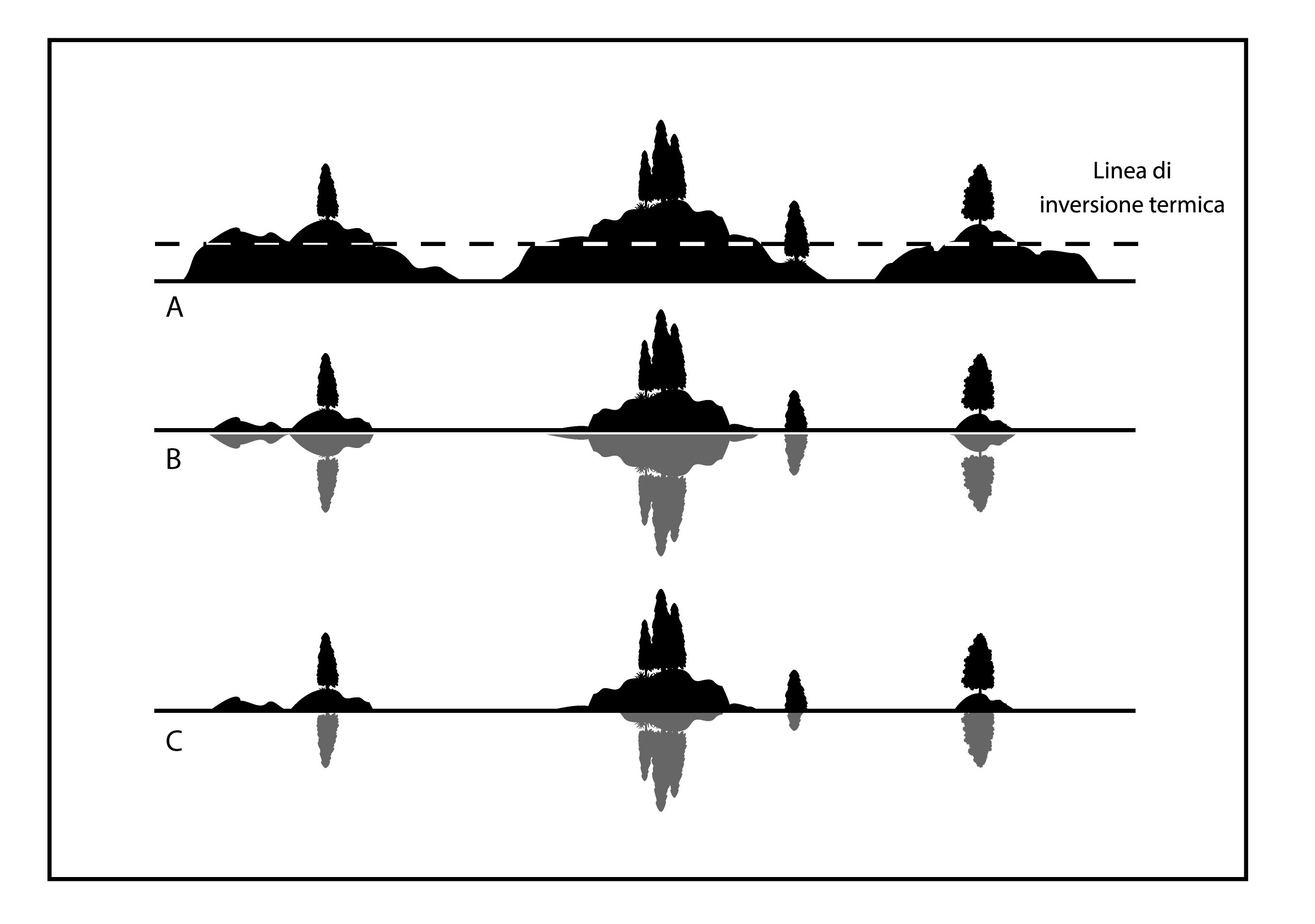

Fata Morgana

Many call it “the mirage”, but it is only a particular case of the vast family of mirages. The Fata Morgana is a rather complex phenomenon, the result of the repeated combination or superposition in a short period of time of several very vivid superior mirages. The different layers of thermal inversion intertwine and mix, generating chaotic deformations. An observer can easily see a figure deforming into a series of pillars, regular columns, arches of an aqueduct until arriving at structures similar to castle towers. The phenomenon seems to manifest itself with greater intensity in the Strait of Messina, on Lake Geneva and on the beaches of New Hampshire.

The name comes from an expression used by Italian navigators in the Mediterranean during the 15th century: the legend tells of a king who, during the medieval invasions, arrived in Calabria and saw Sicily and while he was getting ready to cross the Strait a woman appeared to him. At the same time, the Sicilian shore appeared so close that he thought he could touch it with his hand. He dived in, but this was a deception and so he drowned. The woman was Morgan le Fay, sister of King Arthur, who had learned the art of magic from his rival Merlin the Magician. The Nordic mythology of the Knights of the Round Table had reached Southern Italy thanks to the Normans. Before Morgan le Fay, the phenomenon was associated with the sirens of Greek mythology.

Flying Dutchman

With “Flying Dutchman” it is usual to identify the sighting of a ship floating above the sea horizon regardless of the physical cause: superior mirage, Morgan le Fay or horizon erased by the haze.

Le legend of Green Flash

"... If there is any green in Paradise, it is surely that green, the true color of Hope." This is how the French writer Jules Verne describes the green ray in the sentimental novel Le Rayon Vert of 1882. The writer continues: "... a green ray, but of a marvelous green, of a green that no painter can obtain on his palette, a green of which nature, nor the variety of plants, nor the color of the clearest sea, has ever reported the shade!..."

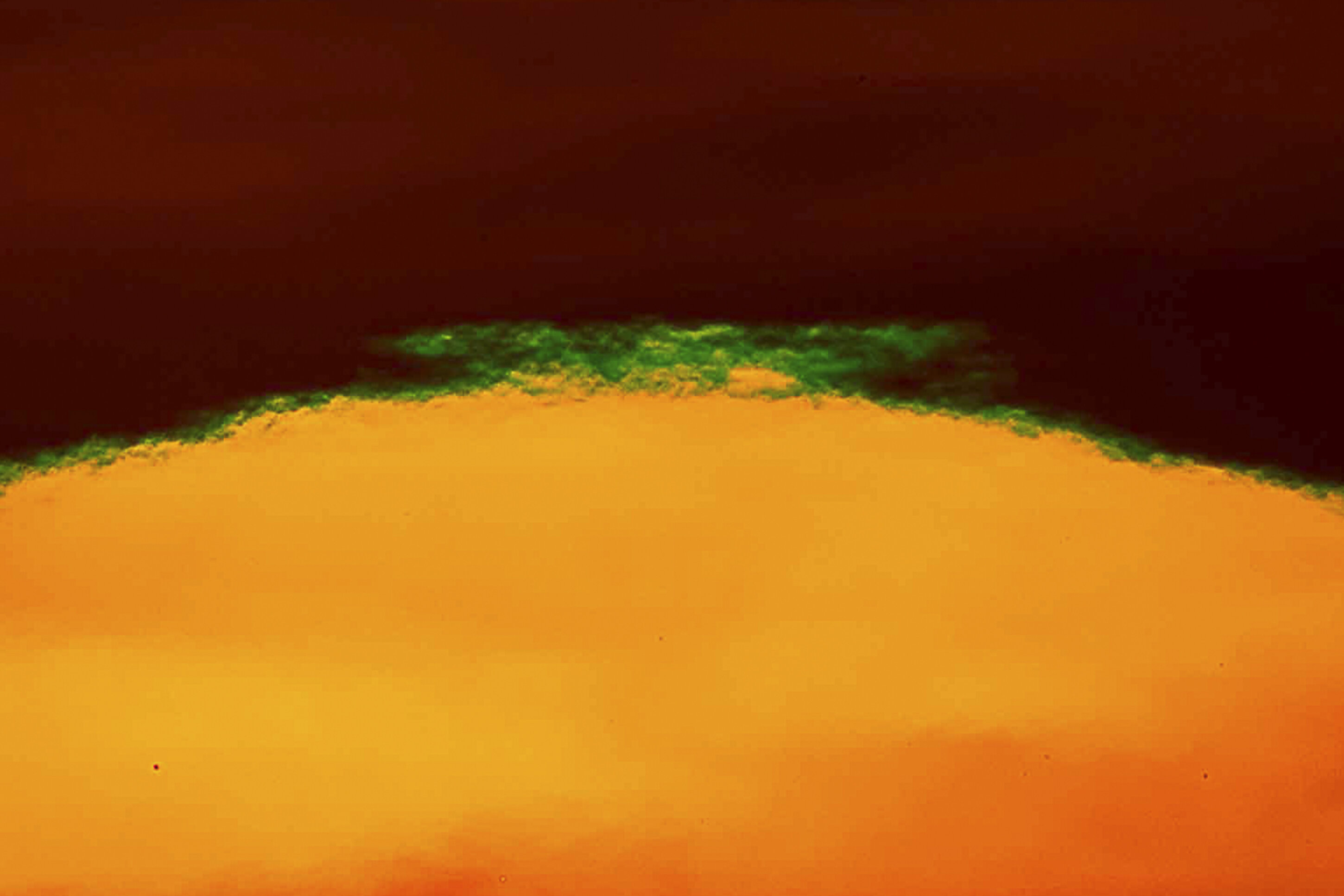

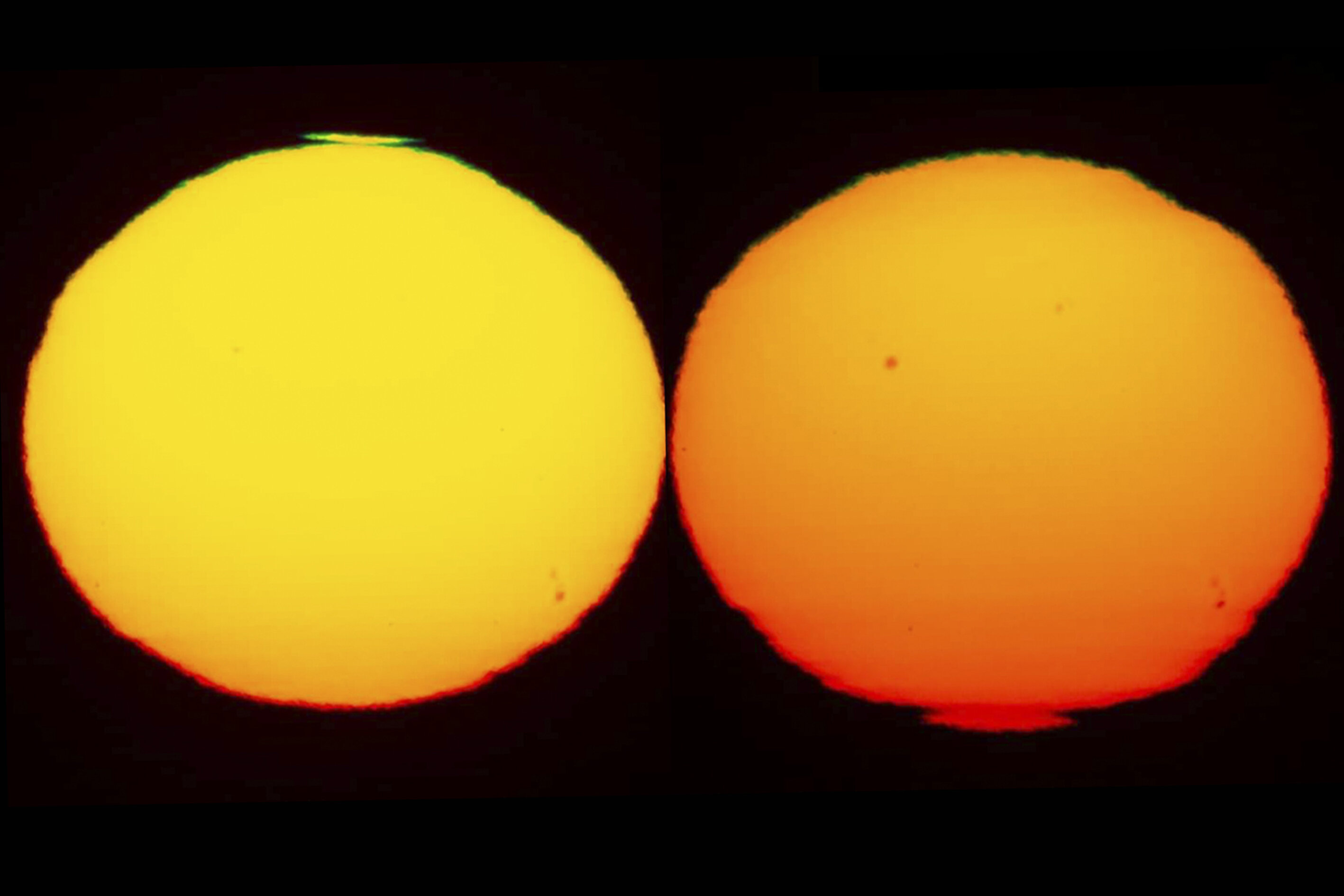

The green ray consists in the vision of a faint green streak, which forms on the top of the solar disk at sunset or at sunrise; in particular conditions, it can transform into a real green flash, or fade into blue/indigo and then transform into the blue ray, but Veronese green is the most common shade. The color is called "Veronese green" in honor of Paolo Veronese, the painter who discovered the pigment.

Green flashes are all due to the effects of variations in astronomical refraction near the horizon. Although there are different types of green flashes, each of these is a by-product of a corresponding mirage and each type is always an enlarged part of the green edge produced by atmospheric dispersion. The main conditions under which the phenomenon occurs are: atmospheric refraction, atmospheric dispersion, diffusion and selective absorption.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study of atmospheric optical phenomena represents a field of fundamental importance for understanding the properties of the atmosphere and light-matter interactions.

To learn more about the topic, we recommend my book “Luci e colori del Cielo”, Ronca Editor 2025.

The book offers valuable advice on how to recognize, observe and photograph atmospheric phenomena. There are explanatory drawings and graphs. In addition, numerous images are proposed from the GrAG Optic Picture of Day column, which collects the best photos from all over the world. Sections on photometeors in the history of art have also been introduced, and QR codes are available to conveniently view museum archives. The volume is intended to be a new and even more complete tool than the first edition. The main topics covered are: rainbows, halo phenomena from atmospheric refraction, photometeors from reflection, dispersion, auroras, mirages, green rays, cognitive illusions, light pollution, seeing, and rare phenomena (sprites, blue goblins, and mysterious lights).

If the first edition was a manual for quick recognition of phenomena, the second volume is intended to be a definitive photographic atlas with an exhaustive text and numerous additional insights.